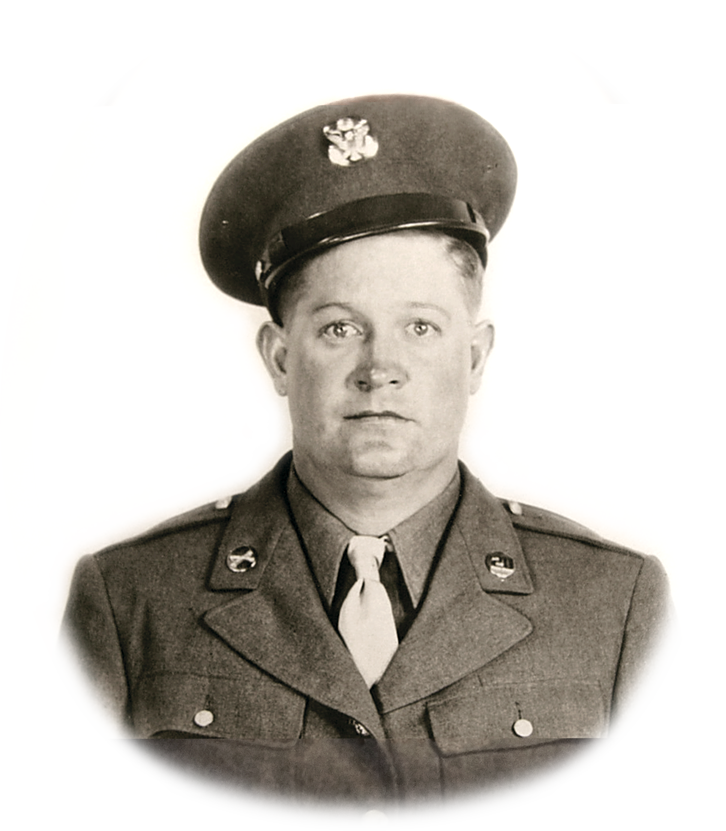

Charlie Monroe Crouse of Cherry Lane in Alleghany County, North Carolina, enlisted in the Army, October 22, 1942, and was assigned to I-Company in the 377th Infantry, 95th Division.

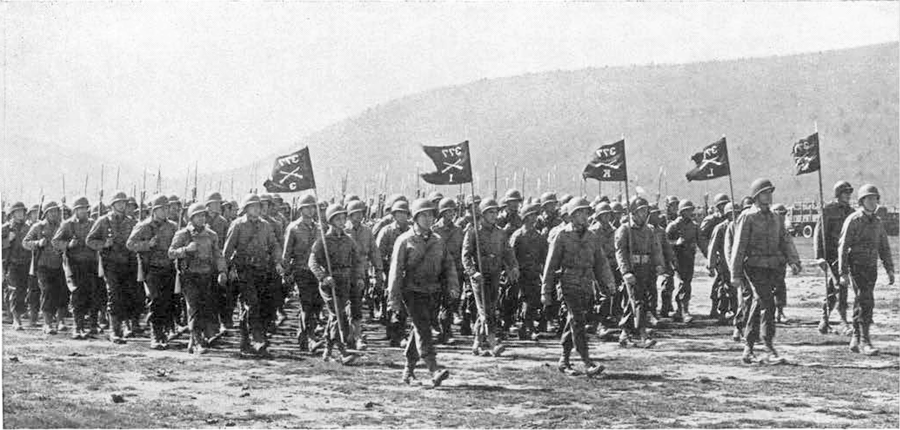

Companies (LtoR) Headquarters, I, K, L, and M.

On July 25, 1944, the Regiment boarded a train for Camp Myles Standish, Mass. where they prepared to embark. Final movement orders arrived and on August 9, 1944, the Regiment boarded a Boston-bound express train and were soon aboard the troopship, USS West Point, and on their way to England.

United States Army, “377th Infantry Regiment” (1946). World War Regimental Histories. 56.

Nine days later they arrived at Liverpool. They traveled by train to Camp Barton Stacey in southern England.

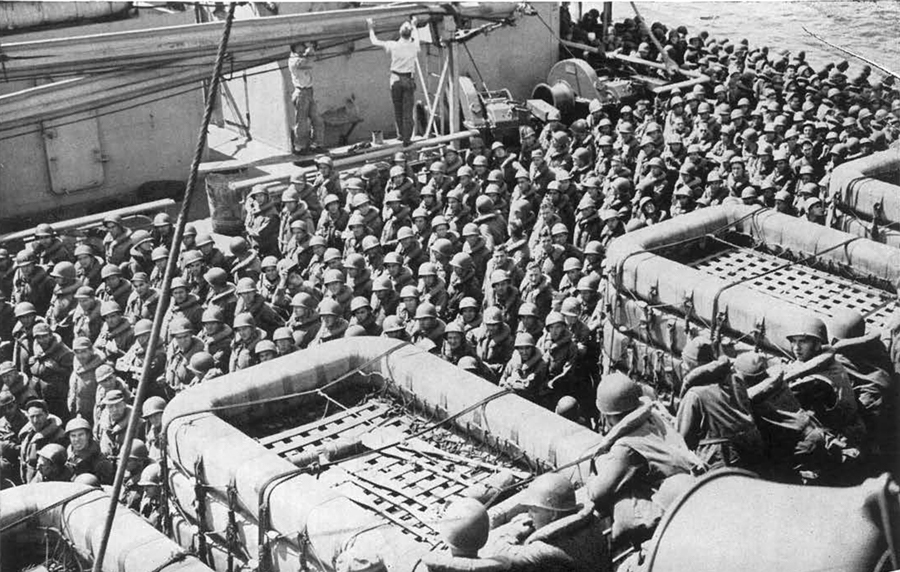

September 6, 1944, the Regiment was again readied for a move to France. Three days later the entire unit moved by train and truck to Southampton, where men and vehicles were loaded to cross the channel on Liberty cargo ships.

United States Army, “377th Infantry Regiment” (1946). World War Regimental Histories. 56.

GEORGE PATTON AND HIS PLAN FOR THE 95TH

On October 9, 1944, the regiment moved across France to Norroy-le-Sec, a small town about 20 miles northwest of the town of Metz.

Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, U.S. Third Army commander, pins the Silver Star

on Private Ernest A. Jenkins of New York City for his conspicuous gallantry in the liberation of Chateaudun, France- NARA– 535724A

On October 15, 1944, they arrived at Barroncourt, 5 miles west of Norroy-le-Sec. Personnel were loaded into trucks which transported them to a bivouac.

Unloading in pitch black darkness in rain and mud, the men stumbled and groped their way into the woods- equipment and all- and bedded down for the night as best they could. All night long, flashes of artillery fire to the east and the distant rumble of guns marked the front lines, about 15 miles away, giving them something to think about and keeping many from getting any rest.

The next morning, companies were organized and settled into their respective areas. Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Commander of the Third Army, visited the Division that afternoon and addressed the officers and non-coms from the various units assembled there. Having heard considerable about the General’s spicy speeches, they were prepared for something out of the ordinary. They were not disappointed. The most emphatic thing he said was to countermand most of what they had been taught for the past two years. The General barked: “There are three ways to die: dig in, lie down, and don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes!”

Patton made a reference in his diary of the 16th:

“After lunch addressed FO’s [Flag Officers] and one officer [and] one NCO [Non-commissioned Officer] from each company in the newly arrived 95 Div.”

The next day, October 17, the Regiment moved to the Forest of Vencheres, where they prepared to relieve the Second Infantry of the Fifth Division on the front lines east of the Moselle River. On the 18th, they proceeded on foot across the river to outpost positions along the Seille River and relieved the front line elements of the Second Infantry. With that move, the regiment officially was in contact with the enemy!

For the entire month of October, men and materiel had been moved forward, in preparation for a new offensive. General Patton’s objective was “to encircle and destroy the garrison of the Metz fortified area and seize a bridgehead over the Saar River.” Before his Third Army could advance, Metz must fall.

Metz was a fortress city throughout history, and it stood in a bend of the Moselle River, ringed by a system of ancient fortresses overlooking a river valley. The junction of the Seille and the Moselle rivers created a deeply etched valley adjacent to the town and provided the German army with one of its best strongholds.

From 1870 until 1918, Metz was a German city and an impregnable fortress that the Allies of World War I had failed to penetrate. In the years between that war and this, the French had modernized the city’s defenses and tied its forts into the Maginot Line, a few miles to the east.

United States Army, “377th Infantry Regiment” (1946). World War Regimental Histories. 56.

The 377th fought its way to the Metz area where I-Company was tasked with the capture of one of these fortified castles, the Chateau Brieux. They achieved their goal in two separate attacks by November 14, losing almost half their strength in the process – about 90 men were casualties, killed or wounded.

U.S. Army Center of Military History

On November 20, I-Company reached the Metz Kaserne (the city garrison) and after taking 52 POWs from a building across the street, they set up to harass the barracks with machine gun and small arms fire. The first I-Company men in the building were told to “watch that building (the Kaserne across the street)- there’s a sniper in it.” Nobody knew it then, but there were about 200 snipers there.

I-COMPANY ATTACKS THE KASERNE

The Kaserne was the nerve center of some of the last German occupiers of the city. Its commanding General had been asked to surrender the garrison but he refused to do so, saying he did not have the authority and that they would fight to the last man.

So, 1st Lt. Mclntryre, I-Company commander, launched an attack early in the morning of the 21st, with M Company’s machine gun section providing cover. The second platoon rushed in and down the basement steps. Before long they were back out again with 200 prisoners who had surrendered as soon as they saw GIs swarming all over the place. The cellar and first floor of the Kaserne were soon under control and prisoners were being rounded up everywhere.

Although it was now safe on the first floor of the garrison, the second and third floor were still enemy strong points and the source of much sniper fire.

Every time a GI would try to go up, they would roll grenades down the steps.

Lt. Taylor tried persuasion and when that failed, he threatened to “blow out the end of the building.”

Getting no results, he had a tank brought up.

The tank made quick work of knocking out one section of the third floor of the building. Resistance began to wane. Their officers were still arrogant though, and insisted on surrendering to an officer. Lt. Geiger took their surrender after he had dug down through about three layers of clothes to find his insignia. “It wasn’t

too healthy to be showing signs of rank in Metz with so many snipers around.”

I-Company moved on to the hospital the night of the 21st and assisted in the evacuation of the city’s highest ranking POW, Generalleutenant Heinrich Kittel, Metz commandant.

At the hospital I-Company had its share of canned fish, chocolate bars, canned fruit and big cakes of cheese with which the place was well stocked.

The Metz operation received considerable publicity in the press, back home which was an important morale factor. The battle proved that the Americans could more than hold their own against the German Wehrmacht (the armed forces of Nazi Germany.)

AFTER METZ: BREAKING THROUGH THE THE MAGINOT LINE

The Second battalion’s troops were dug in along the far edge of the Ottonville woods near Boulay, northeast of Metz. It was where the Third battalion’s mission was to begin the following morning, the 26th. Their objective was to break through the Maginot Line and capture the town of Teterchen, about four miles away.

The terrain for the full four miles was high, rolling and open, with some hedgerows and creeks intervening. All the high ground was commanded by the Germans. A good road and a railway, led northeast to Teterchen.

A broad skirmish line was formed the next morning at 7:30am, with I-Company on the left of the road and L-Company on the right. K-Company were to follow in reserve. Both the mortar and machine gun platoons of M-Company- because the terrain was too open and the situation too uncertain- left their jeeps behind and hand-carried their weapons with the rifle companies.

Finally, the order came and movement forward began. As soon as I-Co. began filtering out from the protective cover of the woods, the enemy sights were on them and mortar shells started landing around them.

1st Lt. Geiger, in command of the company, led his men forward despite the mortar fire. The company opened up with marching fire. “You could see the Kraut observers on the hilltop about a thousand yards in front of us,” related Sgt. Crabtree of the second platoon. “They were in front of us at that distance all day long and they stood right up out there, peering at us with their glasses. They stayed just out of effective range of our small arms but every once in a while we must have got them with our rifles or our mortars. Our mortar section sure saved the day for those of us who did get through the barrage.” The observers would disappear for a moment as the Americans advanced- then reappear on the next hilltop farther back. I-Company’s mortars followed along, firing from the rear.

The German mortar barrage was incessant and it was reported that I-Company was systematically pounded all day long. But the men moved steadily ahead with their blazing hot marching fire. “It was a matter of fighting on or lie there and die,” explained Sgt. McClure. “Many of the reinforcements we’d received just the night before began digging in when the mortar barrage started. Those who did were all casualties. We never even got to know those boys.”

About 4:00 P.M., L-Company sighted their objective, Teterchen, and I-Company, protecting the left flank, pulled up to the rearward side of some high ground facing the town. At last, out of direct observation by the Germans, they dug in.

L-Company men could see the town on a hillside, ringed by trench positions. Sgt. Kid: “We got set and stormed the town, then the Germans came running around the town to our flank. Our heavy machine guns cut them down and the rest of the Jerries withdrew.”

I-Company men remained on the hillside until dark, then filed down to to the road and on into town. In the building that had been set up- the entire company, now was small enough to fit into one building- hot soup and hot water were waiting tor them, courtesy of some high-tailing German officers. The rest of the battalion moved into the town during the night.

Sadly, Pvt. Charlie Monroe Crouse of I-Company had, some time during the day of the 26th, been killed in action.

Plot: K. Row: 34. Grave: 36.

Photo by Beckey Russell & Family

and is located at St. Avold in France.

This article was made from excerpts of the Regimental History of the 377th Infantry which can be found, online, at the Bangor Public Library

Charlie Crouse is listed in the Roll of Honor on page 185 and in the list of FORMER MEMBERS OF THE REGIMENT From 8 October 1943 to 20 October 1945 on page 194.